Inside Marilyn Monroe Reading List: Exploring 3 Key Books and Her Complete Library

- Yana Evans

- Jun 24, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2025

Before we saw her as an icon, Marilyn Monroe was quietly building a personal world behind the camera lights — a world filled with pages, underlined paragraphs, and handwritten notes in the margins. In this section, we’ll dive deep into three of the most pivotal books from her private library. Each one touches on a vital stage in the self-growth process: thinking clearly, loving maturely, and seeing society through a more conscious lens.

These are not simply book reviews. These are moments in a personal evolution — and Monroe is our trendsetter.

Becoming Marilyn: The Making of a Mind Behind the Myth

Marilyn Monroe was born Norma Jeane Mortenson on June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles, California, during one of the most volatile decades in American history. The United States was sliding into the depths of the Great Depression (19T29–1939), a period marked by mass unemployment, widespread poverty, and collapsing social infrastructure. For children born into working-class families — especially those without stable parents — security was a rare privilege.

Norma Jeane’s early life was shaped by instability and institutional breakdown. Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker, worked as a film cutter at Consolidated Film Industries but struggled with paranoid schizophrenia and was eventually institutionalized in 1934, when Norma Jeane was just eight years old. Her father’s identity remains uncertain; his absence became an emotional constant in her life.

With no extended family able or willing to care for her, Norma Jeane was placed in a series of foster homes, orphanages, and temporary guardianships — a common practice at a time when child welfare systems were fragmented and often lacked regulatory oversight. The Los Angeles Orphans Home Society, where she stayed for nearly two years, was known for its crowded conditions and limited emotional support. By her teenage years, she had lived in over ten different homes.

Food was scarce, clothes were borrowed or secondhand, and affection was often transactional. The material realities of the Depression meant she subsisted on government-issued commodities like powdered milk and canned meat. Safety was unpredictable. Her personal recollections hint at instances of emotional neglect and possibly abuse, though Monroe rarely spoke of these in detail.

In 1942, at the age of 16, Norma Jeane married James Dougherty, a 21-year-old neighbor and factory worker. At the time, it was entirely legal in California for girls to marry at 16 with parental consent — a reflection of mid-20th-century norms, particularly for working-class girls seen as nearing adulthood. For Norma Jeane, the marriage was not romantic; it was a legal way to avoid returning to the orphanage, as her foster family planned to relocate out of state.

While Dougherty joined the Merchant Marine during World War II, Norma Jeane worked at a defense plant and was later discovered by a photographer, launching a career in modeling that led her into the studio system of 1940s Hollywood. Her transformation into "Marilyn Monroe" — a stage name crafted by 20th Century Fox — was a collaboration between public fantasy and private resilience.

But behind the curated image of glamour and innocence was a woman engaged in a quiet intellectual rebellion. Monroe assembled a personal library of over 430 books, ranging from classic Russian literature to contemporary philosophy, psychology, and political theory. These books were not decoration — they were tools for self-invention and survival.

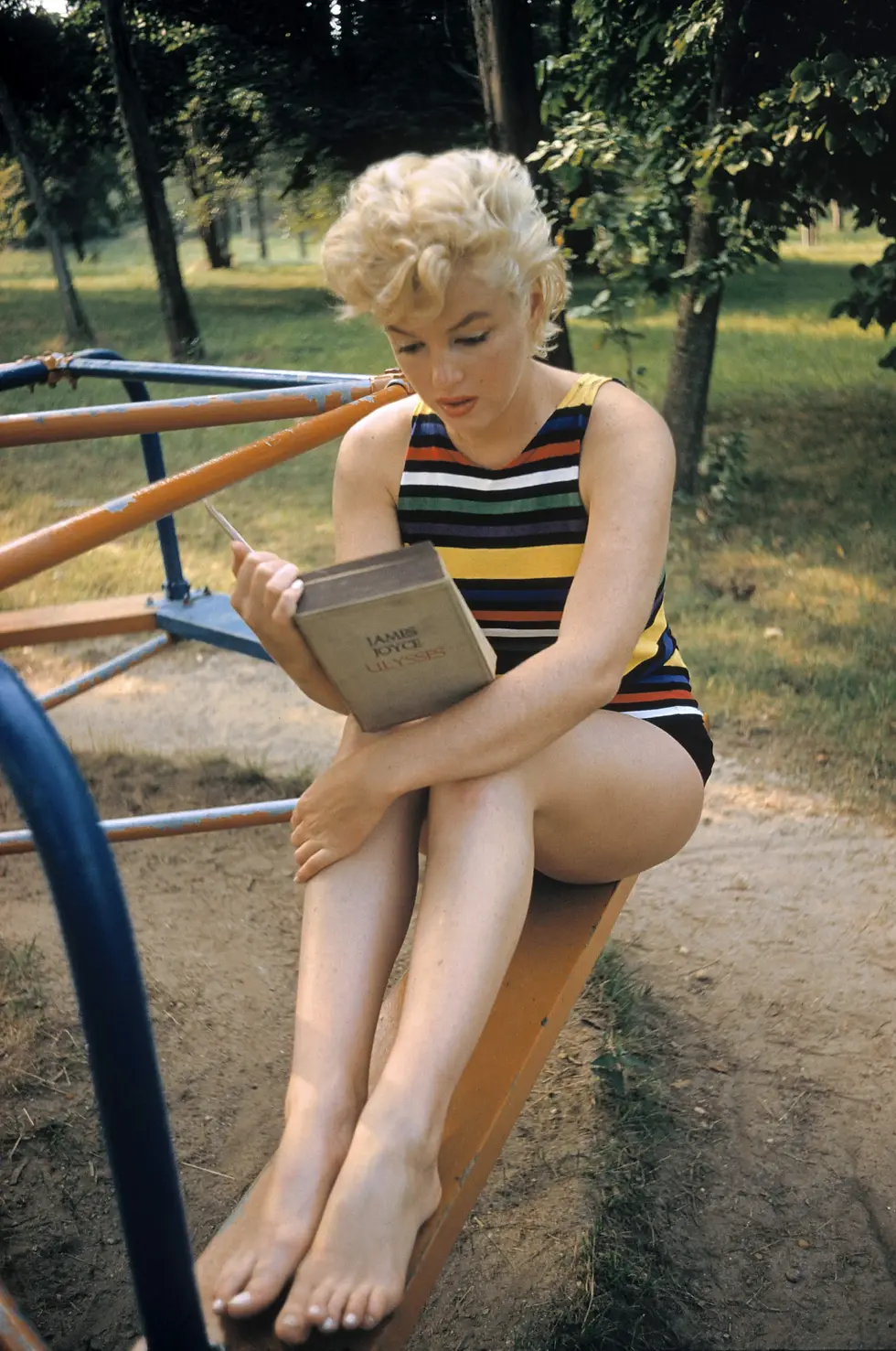

She read on film sets, between takes, and late into the night, frequently annotating margins and revisiting underlined passages. Her bookshelf included titles by Dostoevsky, Proust, Joyce, Freud, Steinbeck, and Rilke — writers whose themes often explored identity, alienation, longing, and self-determination. Her interest in literature may have stemmed from a mixture of curiosity, emotional necessity, and psychological refuge — a way to understand a world that had often failed to understand her.

Psychologists and biographers have speculated that Monroe may have lived with bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder, based on her emotional volatility, episodes of deep depression, and fear of abandonment. Diagnosed terms aside, what emerges is a portrait of someone hypersensitive, intelligent, and profoundly attuned to the invisible emotional landscapes of herself and others.

Were she alive today, Monroe might easily align with INFJ or INFP on the Myers–Briggs typology — the idealist, the advocate, the intuitive seeker who craves authenticity, meaning, and inner coherence in a world of surfaces.

For Monroe, reading was not escape. It was structure in chaos, voice in silence, agency in an industry that tried to erase her interior life. Books gave her a method of re-authoring herself — of becoming not what others projected onto her, but who she wished to be. They became her private university, her diary, her mirror.

In the pages that follow, we will explore three works from her personal library that reflect the scope of her inner evolution: from mental clarity (How to Develop Your Thinking Ability), to emotional maturity (The Art of Loving), to social awakening (Invisible Man). Together, they map a path of development that remains timeless — and eerily resonant for anyone navigating identity, vulnerability, and truth.

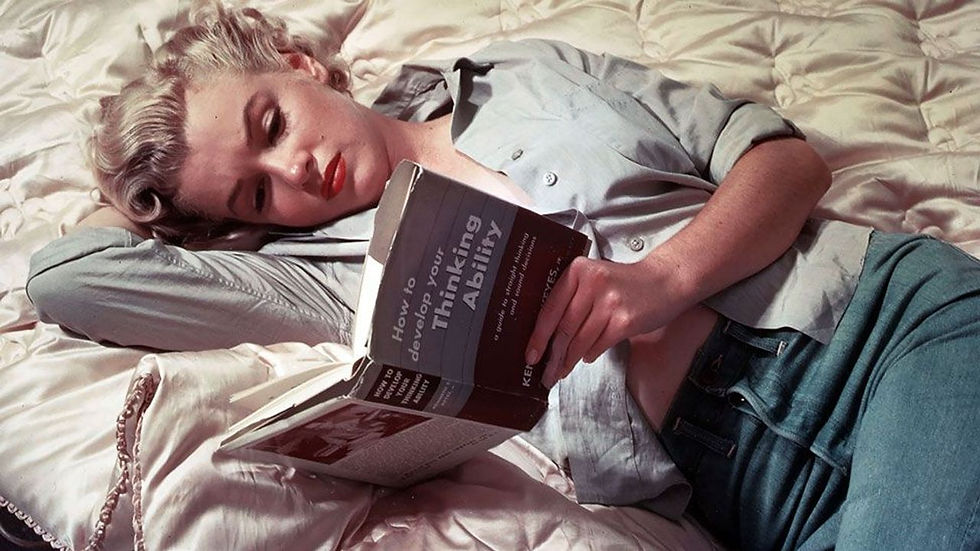

How to Develop Your Thinking Ability by Ken Keyes Jr.

How to Develop Your Thinking Ability by Ken Keyes Jr. and William Frank, first published in 1950, offered readers a methodical approach to mental self-discipline at a time when such resources were rare outside academic settings. Positioned against the backdrop of postwar America — a period of rapid industrial growth, standardized education, and increasing psychological inquiry — the book reflected a growing cultural desire for personal development through cognitive clarity.

The early 1950s were shaped by optimism and anxiety in equal measure. While the nation was rebuilding itself economically and technologically, individuals were grappling with the psychological aftermath of war and the pressures of social conformity. Psychology was beginning to enter public consciousness through simplified frameworks, and books like this one translated emerging theories of cognition and learning into structured exercises for ordinary readers. Keyes and Frank were not academic psychologists but succeeded in distilling principles aligned with critical thinking and problem-solving in a way that felt immediately useful.

At its core, the book trains the reader to examine assumptions, define problems with precision, and work through ambiguity without defaulting to emotional reactivity. Its methods include comparative analysis, reframing questions, and articulating multiple perspectives—skills that later became fundamental in cognitive psychology and decision-making research.

The difficulty of engaging in such intellectual work lies not just in the content but in our biology. Human cognition evolved to prioritize energy conservation and survival; abstract reasoning and prolonged attention are metabolically demanding and, from an evolutionary standpoint, offered no immediate advantage. As a result, much of our default thinking operates on shortcuts—what modern psychologists call heuristics. To interrupt these patterns requires intentional effort and long-term discipline.

That Marilyn Monroe chose to study this material is a telling reflection of her private ambition to transcend surface perceptions. Known publicly for her image, she privately pursued structure and insight. For someone constantly objectified, mental clarity became a form of autonomy.

Keyes would go on to write more philosophically inclined works, but this early guide remains a singular example of accessible cognitive training. For modern readers interested in further depth, related scientific works include Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, Keith Stanovich’s research on rationality, and Richard Nisbett’s studies on inductive reasoning.

In a culture of speed and spectacle, How to Develop Your Thinking Ability reminds us that clarity of thought is neither innate nor easy—but it is a skill that can be trained, and one that quietly defines the course of a life. Marilyn understood this. Her attention to thinking was not an intellectual fashion but a survival strategy, and ultimately, a philosophy of self-determination.

Together with Keyes’ practical foundation, these works help build a mental toolkit — not only to understand the world better, but to see oneself more clearly within it.

Example Exercises from the Book

Here are a few exercises Ken Keyes Jr. offers to develop thinking ability:

Distinguish Similar from Different

Exercise: Look at two objects or ideas that seem similar. List ways they are alike and ways they differ. Practice noticing fine differences rather than assuming sameness.

Purpose: Train perception and reduce mental oversimplification.

Question Assumptions

Exercise: Pick a belief you hold strongly. Write down the reasons you believe it. Then list possible reasons it might be wrong.

Purpose: Encourage open-mindedness and critical thinking.

Problem Restatement

Exercise: When faced with a problem, restate it in multiple ways to gain new perspectives.

Purpose: Break mental fixation and uncover hidden aspects.

Divide and Conquer

Exercise: Take a complex issue and break it into smaller parts. Address each part individually before synthesizing.

Purpose: Improve analytical clarity and prevent overwhelm.

Additional literature to read and explore:

Daniel Kahneman – Thinking, Fast and Slow

A foundational text on the two systems of thinking: fast, intuitive reasoning vs. slow, deliberate analysis.

Carol Tavris & Elliot Aronson – Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)

An accessible look at cognitive dissonance, denial, and the inner mechanics of self-justification.

Keith Stanovich – What Intelligence Tests Miss

Explores why intelligence alone isn’t enough — and why rational thinking matters more than IQ.

Edward de Bono – Lateral Thinking

Techniques for creative problem-solving and disrupting fixed patterns of thought.

Steven Pinker – The Blank Slate

Investigates human nature and built-in cognitive tendencies that influence how we process the world.

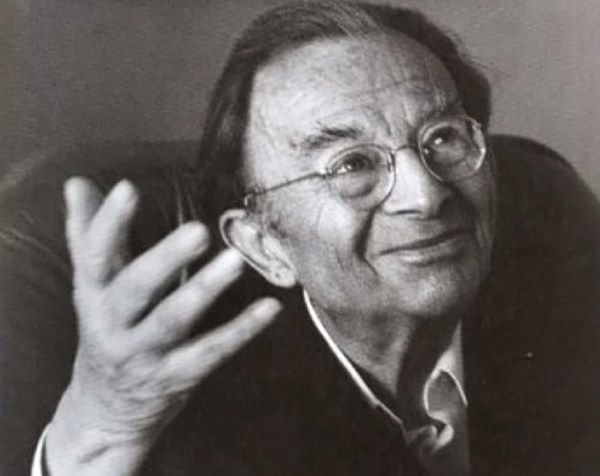

The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm

“Love is the only sane and satisfactory answer to the problem of human existence.”

The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm was published in 1956 during a period of substantial cultural and psychological transition in the post-war Western world. Fromm, a trained psychoanalyst and social philosopher, sought to reframe the popular discourse on love by challenging prevailing assumptions rooted in both mass culture and classical psychoanalysis. His work responded to the rapid modernization of society, the increasing commodification of human relationships, and the psychological consequences of living in a highly industrialized, status-driven world.

Born in Frankfurt in 1900, Fromm was a central figure in the Frankfurt School—a group of thinkers including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse—whose interdisciplinary approach merged Marxist sociology, psychoanalysis, and critical theory. Fromm later diverged from the School’s emphasis on historical materialism to develop a more humanistic and ethical psychoanalytic model. Influenced by thinkers such as Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, Meister Eckhart, and Jewish mysticism, Fromm constructed a theory of the individual that emphasized autonomy, ethical responsibility, and the capacity for productive love.

Fromm wrote The Art of Loving against the backdrop of the Cold War and the rise of American consumer culture, where identity was increasingly constructed through acquisition and external validation. In psychological terms, this period saw a growing popularity of behaviorism and mechanistic views of the mind, which Fromm resisted. He viewed love not as a spontaneous emotional event or as an instinctual drive, but as a complex ethical and psychological capacity requiring self-discipline, maturity, and sustained attention.

Fromm’s central thesis is that love is an art—akin to learning music or architecture—requiring not only passion, but also theory, effort, and lifelong practice. He categorized love into several distinct forms: brotherly love, motherly love, erotic love, self-love, and love of God, each with its own psychological structure and function. He warned against the illusion of romantic love as a passive occurrence, critiquing the contemporary tendency to treat love as a market commodity—chosen as one might select a product, based on appeal and exchange value.

For a reader like Marilyn Monroe—whose life was shaped by systemic abandonment, transient relationships, and the often-predatory dynamics of the film industry—Fromm’s emphasis on love as a practiced discipline rather than an emotional accident may have provided an intellectual framework for interpreting her personal experiences. The book’s psychoanalytic foundation, coupled with its ethical tone, positioned it not as a self-help guide but as a structural critique of emotional immaturity and false ideals.

The rigor of Fromm’s argument lies in its demand for self-knowledge as a precondition for the capacity to love. He asserts that one must first overcome narcissistic distortions, confront their existential aloneness, and accept the paradoxes of human freedom before love becomes psychologically viable. His insistence on love as an act of will and ethical responsibility stands in direct opposition to Freudian fatalism and the sentimentality of popular culture.

The enduring relevance of The Art of Loving can be attributed to its integration of psychoanalytic thought with existential philosophy and ethical psychology. It remains one of the few mid-20th-century texts that treats love as both an individual and collective human task. For those interested in going deeper, complementary works include Rollo May’s Love and Will (1969), Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (1946/1959 in English), and contemporary studies in attachment theory by John Bowlby.

For Monroe, who invested herself in psychological study amid an increasingly dehumanizing public role, Fromm’s work may have served not only as a theoretical interest but as a reflective instrument. Through his model, she would have encountered a framework that refused sentimentality and instead demanded clarity, ethical resolve, and conscious growth—qualities she pursued in private, even as her public image suggested the opposite.

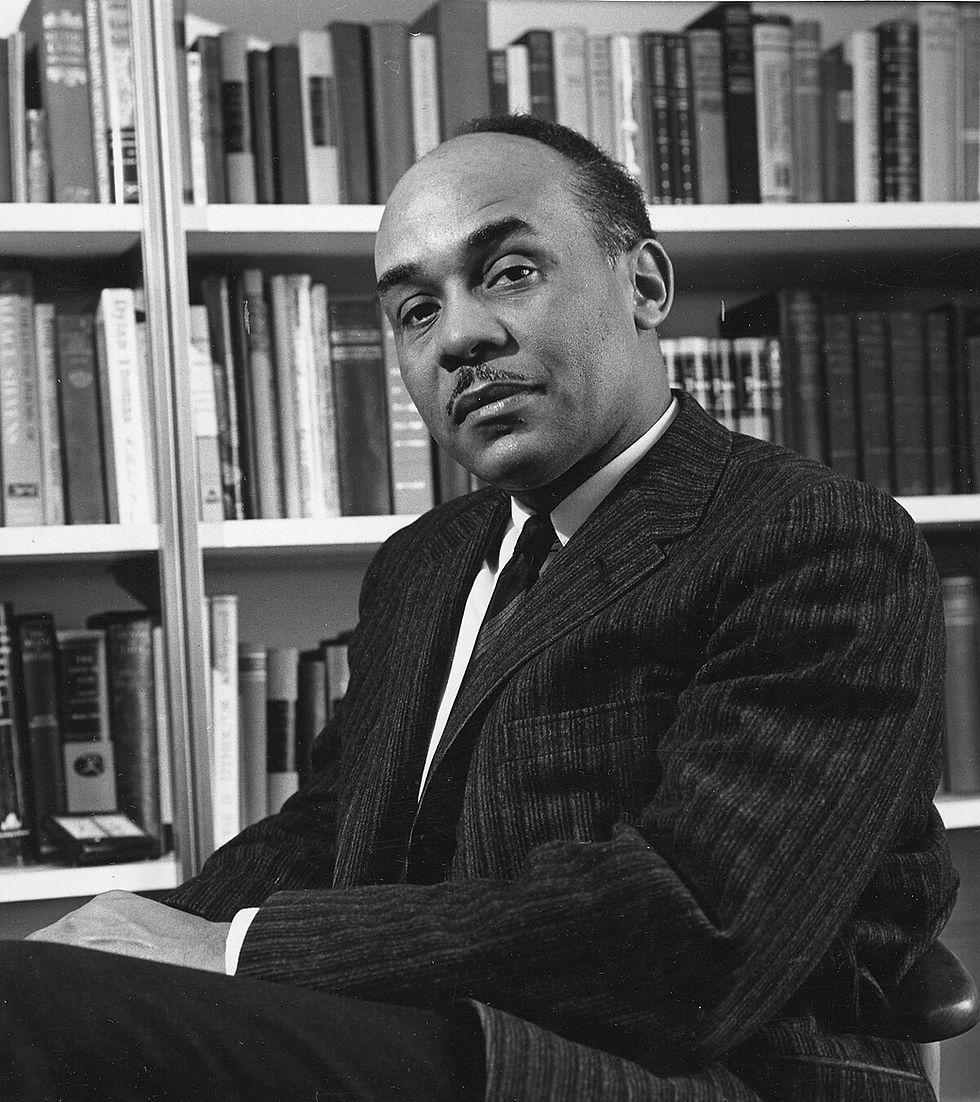

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Published in 1952, Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison quickly established itself as a landmark in American literature. Set against the backdrop of the early 20th century, particularly the interwar and postwar periods, the novel examines complex questions of identity, power, and social invisibility through the life of an unnamed African American narrator. It explores how individuals can be rendered unseen—not physically, but in terms of agency, recognition, and voice—by the social systems and cultural expectations that define their environment.

Ellison, born in 1914 in Oklahoma City, developed his voice during the intellectual aftermath of the Harlem Renaissance and was influenced by a wide literary and philosophical tradition. These influences included T.S. Eliot, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and existentialist thought, as well as his early association with Richard Wright and the broader realist movements in African American literature. However, Ellison took a different direction than his predecessors, blending modernist literary techniques, psychological depth, and elements of folklore and jazz structure to create a highly nuanced narrative voice.

Invisible Man is not a straightforward social novel; it is deeply philosophical, shaped by the postwar context in which it was written. The 1940s and early 1950s were marked by ideological tensions, increasing conformity in American culture, and the early stages of the Cold War. In this atmosphere, Ellison’s exploration of personal autonomy, ideological manipulation, and social fragmentation resonated far beyond the specific racial experiences of his protagonist.

Marilyn Monroe’s decision to include this novel in her personal library demonstrates an engagement with serious, complex literature that reached far outside the realm of typical celebrity culture. Although Monroe did not publicly comment on the book, her private interest in such a challenging and politically layered text suggests intellectual curiosity and a willingness to confront ideas that were not mainstream reading for public figures in the 1950s.

It would be inappropriate to draw direct parallels between Monroe’s life and the racial themes at the center of Invisible Man. However, what can be acknowledged is a shared interest in the broader question of visibility and identity—how individuals are perceived by society versus how they perceive themselves. The novel’s treatment of imposed roles, projection, and internal alienation may have offered Monroe a meaningful framework for reflecting on her own experiences within the entertainment industry, which often reduced her to an image rather than a person.

The significance of Invisible Man also lies in its literary structure. Rather than offering a clear resolution, the novel insists on complexity and ambiguity, refusing to reduce its characters to symbols. It is this insistence on complexity that has kept the novel in academic and literary discussion for decades. It remains widely taught in university literature and political theory courses and is often paired with broader philosophical works dealing with subjectivity and recognition.

For readers interested in further exploring the themes presented in Invisible Man, complementary texts might include James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, or W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk. These works engage with questions of individual freedom, social structures, and cultural identity—central issues of the 20th century and still relevant today.

Ultimately, Monroe’s inclusion of Ellison’s novel in her personal collection invites us to view her not only as a cultural icon, but as a thoughtful reader—one who engaged seriously with the intellectual and moral challenges of her time, even those far removed from her own background or direct experience.

Selected Titles from the Marilyn Monroe Reading List

The Marilyn Monroe reading list includes over 430 books from her personal library, offering a glimpse into her rich inner world. The selection below highlights confirmed titles from her collection, though it does not represent the full extent of her reading. Some books remain uncatalogued or lost, while others are known only through photographs or firsthand accounts.

Novels & Fiction

Ulysses — James Joyce

The Fall — Albert Camus

Anna Karenina, War and Peace — Leo Tolstoy

Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov — Fyodor Dostoevsky

Madame Bovary — Gustave Flaubert

Swann’s Way, Within a Budding Grove, The Guermantes Way, Cities of the Plain, The Captive — Marcel Proust

The Great Gatsby, Tender Is the Night — F. Scott Fitzgerald

A Farewell to Arms, The Sun Also Rises — Ernest Hemingway

On the Road — Jack Kerouac

Tortilla Flat, The Short Reign of Pippin IV, Once There Was a War — John Steinbeck

Invisible Man — Ralph Ellison

The American Claimant & Other Stories, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Roughing It — Mark Twain

Sons and Lovers, Selected Poems — D.H. Lawrence

Death in Venice & Other Stories, Last Essays — Thomas Mann

Look Homeward, Angel, The Story of a Novel, Letters to His Mother — Thomas Wolfe

Winesburg, Ohio — Sherwood Anderson

Sister Carrie — Theodore Dreiser

Lie Down in Darkness, Set This House on Fire — William Styron

Hawaii — James Michener

Camille — Alexandre Dumas

The Magic Christian — Terry Southern

A Death in the Family — James Agee

Drama & Plays

A Streetcar Named Desire, Camino Real, The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone — Tennessee Williams

Long Day’s Journey Into Night — Eugene O’Neill

Plays by Arthur Miller, George Bernard Shaw, Clifford Odets, Sean O’Casey, Eugene O’Neill

Antigone — Jean Anouilh; Medea — Robinson Jeffers

Bell, Book and Candle — John Van Druten; The Women — Clare Boothe

Philosophy & Thought

The Prophet — Kahlil Gibran

Works by Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre

Civilization and Its Discontents, The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychology of Everyday Life — Sigmund Freud

The Open Mind, Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare — J. Robert Oppenheimer

The Philosophy of Schopenhauer, Spinoza

The Golden Bough — James Frazer; The Rights of Man — Thomas Paine; works by Plato, Aristotle, Lucretius

Poetry & Short Works

Leaves of Grass — Walt Whitman; The Portable Whitman

The Portable Poe — Edgar Allan Poe

Selected Poems — Emily Dickinson, D.H. Lawrence, Rainer Maria Rilke

Works by Dorothy Parker, Carson McCullers, Colette, Lorenzo Garcia Lorca

Biographies & Non-Fiction

The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens; Carl Sandburg’s 12-volume Abraham Lincoln biography

The Little Prince — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The Bible

How to Travel Incognito — Ludwig Bemelmans; travelogues about India, Rome, London, Russia

The New Joy of Cooking, The Boston Cooking‑School Cookbook

Works on anatomy, music appreciation, art—Beethoven, Schubert, Michelangelo, Goya

Miscellaneous & Self-Help

Sexual Impotence in the Male, The Thinking Body, The Actor Prepares, To the Actor

Everyman’s Search, How to Develop Your Thinking Ability, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures

Light reading: The Little Engine That Could, Pet Turtles, The Joy of Cooking, cookbooks and domestic guides