Interpretive Portraiture and Other Types of Portrait Art: Why Emotion Matters More Than Likeness

- Yana Evans

- Aug 5, 2025

- 13 min read

CONTENTS:

Art lovers and newcomers alike often grapple with the difference between realistic and expressive art and types of portrait art. Many assume that a “good” portrait must precisely resemble a photograph. This common confusion between realism and expressionism can lead viewers to overlook a portrait’s deeper meaning. In reality, interpretive portraiture bridges these worlds – it embraces the artist’s personal vision and emotional insight rather than just copying what the eye sees. In this post, we will clarify what interpretive portraiture means, why likeness is not its primary goal, and how it conveys truths that a straightforward likeness cannot. You’ll discover a bit of art history (from Egon Schiele to Lucian Freud), learn why distortions or abstractions can reveal more than realism, and see a modern example that illustrates the power of interpretive portraiture. By the end, you’ll understand why this approach to portraiture matters more than you might think, encouraging you to look beyond surface likeness and into the story a portrait tells.

What Is Interpretive Portraiture?

Interpretive portraiture is a form of artistic portraiture that prioritizes personal expression and deeper meaning over exact visual fidelity. Rather than aiming for a photographic likeness, an interpretive portrait filters the subject through the artist’s subjective vision – exaggerating, distorting, or abstracting features to communicate something essential about the person. As contemporary painter Caren Ginsberg describes, this approach focuses “on the emotion, movement, and art of a being, rather than a simple likeness”. In practice, interpretive portraitists use inventive techniques (stylized lines, altered proportions, symbolic elements, unconventional colors) to convey how the subject feels or signifies to them, not merely how the subject appears to the eye. This gives the artwork a conceptual or emotional truth that a straightforward copy might not capture.

From an academic perspective, interpretive portraiture can be understood through visual semiotics and the psychology of perception. A traditional realistic portrait operates as an iconic sign – it directly resembles the subject – whereas an interpretive portrait often introduces symbolic or expressive signs that require the viewer’s interpretation. For example, an artist might elongate a figure’s limbs to suggest grace, or surround a visage with chaotic brushstrokes to signify turmoil. These deliberate deviations from reality engage the viewer’s mind: we instinctively look for the meaning behind the “distortions.” Far from being arbitrary, such distortions are used to reveal facets of the subject’s character, mood, or story that a literal likeness might overlook. In this sense, interpretive portraiture aligns with the idea that art’s purpose is not to mirror the world, but to illuminate truths about it – sometimes the inner truth of a person – through imaginative representation.

Historical Context and Types of Portrait Art (Schiele, Picasso, Kollwitz, Freud)

Interpretive portraiture as we know it took shape in the modern era, when many artists began to rebel against the strict realism that had dominated academic art. Early 20th-century portraitists in particular felt that conveying the inner life of their subjects was more compelling than reproducing a polished outward likeness. This mindset can be seen in the work of artists like Egon Schiele, Pablo Picasso, Käthe Kollwitz, and Lucian Freud – each of whom, in different ways, broke the rules of traditional portraiture to express something deeper.

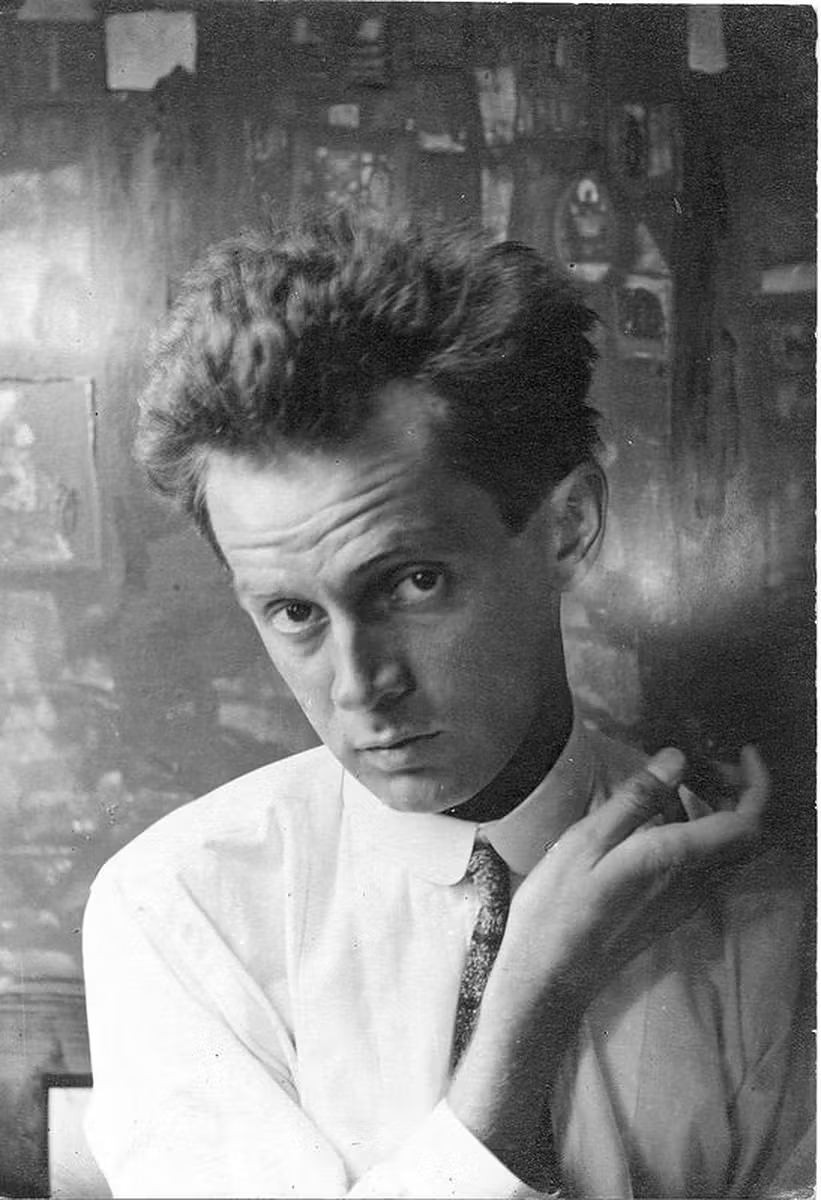

Egon Schiele (1890–1918)

Egon Schiele (1890–1918) the Austrian Expressionist, is a key early example. Schiele’s portraits and self-portraits are characterized by a signature figural distortion and an almost raw emotional intensity. He boldly defied conventional norms of beauty and proportion: bodies and faces in his works appear emaciated, angular, and contorted in unnatural poses. This was quite intentional – Schiele was “embracing figural distortion” as a tool, creating what one curator calls “searing explorations” of his sitters’ psyche and sexuality. In a self-portrait from 1911, for instance, the artist depicts himself with a gaunt, twisted torso and a wild, haunted gaze. The agitated pencil lines and exaggeration of certain body parts (like enlarged eyes and a skeletal frame) externalize a feeling of inner tension and spiritual torment. Such images are not flattering likenesses; rather, they lay bare Schiele’s subjective experience of human anxiety and desire. By sacrificing anatomical accuracy, Schiele heightened the emotional impact – his portraits confront the viewer with the sitter’s inner turmoil in a way a smooth academic painting never could.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) provides another famous early case. Picasso’s approach to portraiture evolved dramatically over his career, but even in his pre-Cubist works he was already veering away from strict realism.

An early example is Head of a Woman (Fernande) (1909), a portrait of his lover Fernande Olivier. The face in this painting is “mask-like and moody,” recognizably Fernande yet heavily stylized – in fact, it’s described as “a more interpretive, less realistic, likeness” . Picasso exaggerated her features (a huge rounded forehead, enlarged ears, an elongated nose and pointy chin) and gave her an inscrutable expression reminiscent of an ancient wooden sculpture. These distortions were influenced by Picasso’s exposure to non-Western (Iberian and African) art, and they imbued the portrait with an exotic, enigmatic presence beyond the literal appearance of Fernande.

A few decades later, Picasso’s cubist and expressionist portraits pushed distortion to extremes that shocked his contemporaries. His portraits of Dora Maar in the late 1930s (such as Weeping Woman, 1937) famously twist facial features almost beyond recognition – eyes misaligned, profile and front views spliced together, noses like sharp snouts. Critics and viewers were polarized, asking how an artist could look at a person and “see her in this way”. Yet Picasso’s aim was not to document Dora’s surface traits, but to portray her psychological complexity – her anguish, multifaceted personality, and Picasso’s own tumultuous feelings about her. What looks like fragmentation and “wrong” perspective is actually a composite truth: Picasso shows his subject from multiple angles at once (literal and metaphorical), suggesting that a person cannot be fully understood from one static view. It’s important to note that Picasso was perfectly capable of painting in a lifelike manner – early in his career he produced realist portraits with academic skill – but he “wasn’t satisfied” with mere visual realism. Restlessly seeking new means of expression, he treated naturalistic likeness as just one option among many. His distorted portraits, far from mistakes, were calculated departures from reality to convey a more profound vision of his subjects.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945)

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), a German printmaker and draftsman, offers a slightly different angle in the historical development of interpretive portraiture. Kollwitz was associated with German Expressionism, although her style remained grounded in figurative representation. Her works – often focusing on poverty, grief, and the human toll of war – are renowned for their emotional depth and empathy. In her self-portraits especially, Kollwitz did not idealize herself or soften the truth of her feelings. A striking example is her Frontal Self-Portrait woodcut from 1922–23, which confronts the viewer with an almost stark honesty. The face is rendered as “a mask-like web of searing lines and forceful strokes,” etched with weariness. Kollwitz presents her own visage as aged, “raw and weathered,” an “emblem of sorrow” that perfectly encapsulates the depth of emotion defining her work. In this portrait, fine detail is less important than overall impression – the eyes are dark and haunted, the hand touches the forehead in a gesture of despair. The distortion here is subtle but powerful: Kollwitz exaggerates the harsh contrasts and deep creases of her face, essentially carving her grief into the block and paper. By foregoing prettiness and exactitude, she communicates profound inner experience – the personal and collective suffering of her times – with an almost iconic simplicity. Her interpretive approach shows that likeness can be psychological and symbolic: she looks recognizably herself, yet the image operates on a universal level, evoking compassion and anguish that any viewer can feel.

Lucian Freud (1922–2011)

Moving into the mid-20th century, Lucian Freud (1922–2011) carried the torch of interpretive portraiture in a unique way. Freud, the British painter (and grandson of Sigmund Freud), is often described as a realist because of his meticulous, observational technique – he painted directly from life with unflinching detail. Yet Freud’s brand of realism was so brutally honest and probing that it transcended mere likeness and became something profoundly psychological. He famously said, “I paint people not because of what they look like, but despite it.” In Freud’s portraits, every wrinkle, sag, and blemish of the sitter’s flesh is scrutinized; he often chose models with distinctive or imperfect bodies and posed them in unguarded, sometimes awkward positions. The result is a kind of hyper-real truthfulness that can be unsettling. A profile of Freud notes that his paintings are “rich in psychological intensity and raw physicality, offering an intimate glimpse into both the sitter’s exterior and inner world” .

Indeed, Freud’s hallmark was the unembellished human form – he refused to flatter or stylize his subjects in the conventional sense, yet in doing so he achieved a deeper interpretation of their character. Consider his portrait of an aging benefits supervisor asleep nude on a couch (Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, 1995): the sheer corporeal mass of the figure, rendered with almost clinical precision, paradoxically conveys vulnerability and humanity. By emphasizing the unidealized reality of the body, Freud invites the viewer to contemplate the subject’s inner life – her dignity, fragility, and the passage of time inscribed on her form. Thus, even though Freud did not “distort” in an overtly abstract way like Picasso did, his work is highly interpretive. It demonstrates that interpretation isn’t only in exaggeration; it can also be in the intense emphasis or focus an artist chooses. Freud’s commitment to portraying the truth of the human condition – warts and all – means his portraits go beyond replication. They convey the sitter’s psychological presence with a force that a polite, photographic likeness would not match.

In summary, from Schiele’s twisted figures to Picasso’s fractured faces, Kollwitz’s wrenching visages to Freud’s penetrative studies, art history furnishes a rich context in which interpretive portraiture emerged as a powerful alternative to pure realism. These artists showed that a portrait can diverge from optical reality and yet achieve a different kind of truth – one that resonates with viewers’ emotions and understanding of the human experience.

Why It’s Not About Likeness

Given the examples above, it becomes clear that technical likeness – making the painting look exactly like the person – is not the ultimate goal of interpretive portraiture. But why not? The rationale lies in the distinction between capturing appearances and conveying deeper truths. Interpretive portrait artists seek to capture the essence of a subject, which may involve their emotions, personality, context, or significance, rather than a surface-level resemblance. In pursuing this, they intentionally manipulate form and feature.

As a scholarly analysis of Francis Bacon’s portraits observes, what outsiders might label “distortions” are only errors if one assumes the artist’s aim was a perfect copy of reality. In Bacon’s case, that was not his aim at all.

To illustrate: if Bacon had intended to paint a physically accurate likeness of Pope Innocent X (the subject of one of his famous works) we would say he “failed miserably.” However, “if instead Bacon intended to represent a nightmarish image which seethes with aggression, and yet communicates the inherent isolation of the pontiff’s position, then his work is perfectly accurate.” In other words, a portrait must be judged against what it set out to depict. Bacon did not want us to see a polite 17th-century pope; he wanted us to feel the terror and claustrophobia of absolute power. From that standpoint, the screaming, blurred figure he painted is a success – it communicates exactly those emotional truths.

The lesson generalizes to all interpretive portraiture: distortion does not equate to misrepresentation. When an artist purposefully elongates a neck, shifts an eye, or uses an unreal color, it isn’t a mistake; it’s a message. The portrait is telling a truth on a different level, often a psychological or symbolic truth, which may be impossible to convey through literal resemblance alone.

Intriguingly, findings from psychology support the idea that recognizability and literal accuracy are not the same thing. Our brains do not process faces like a computer scanning a photograph; we latch onto key features and their relative differences. Research on caricatures – portraits that deliberately exaggerate distinctive features – has shown that people can actually recognize a face more quickly or easily from a well-done caricature than from an exact photograph. In one classic study, caricatures, though “gross distortions of faces,” often acted as “super-portraits” that elicited better recognition than undistorted images of the same individuals. The caricature works by amplifying what is unique about someone (say a strong chin or high forehead), thus capturing their identity in a concentrated way. This counterintuitive result underscores the central point: faithfully reproducing every detail of a face is not always the best way to capture what makes that person that person. Interpretive portraitists intuitively leverage this principle.

By exaggerating a signature feature or simplifying less important ones, they guide the viewer’s attention to the traits or moods that matter most. The outcome can feel truer than a photograph, because it reflects the artist’s insight into the subject’s identity. In sum, interpretive portraiture is not about likeness in the narrow, mechanical sense; it’s about a deeper likeness – one of character, spirit, or narrative. As Picasso famously said, “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth”. The “lie” of not reproducing a face exactly can reveal a more profound human truth to the viewer. The measure of success is not, “Does this look exactly like so-and-so?” but rather, “Does this portrait make us understand or feel something about so-and-so (or about ourselves, or about life) that a mere mirror image would not?”

Modern Misunderstandings

Despite a long artistic tradition of expressive and interpretive portraiture, there are still common misunderstandings about this art form in the modern era. In popular culture – especially in an age saturated with photography and high-definition images – many people instinctively equate a “good” portrait with an exactingly realistic one. It’s not uncommon to hear an uninitiated viewer judge a portrait by how closely it resembles a photograph of the subject, as if the two were the same thing. Such expectations have led to misplaced criticism of interpretive works. When confronted with a boldly distorted or stylized portrait, a casual observer might react with confusion or dismissal: “That doesn’t look like the person at all!” or “My camera could do a better job.” This knee-jerk response is not new – even Picasso’s revolutionary portraits were met with bafflement and ridicule by some viewers. An anecdote from the 1930s recounts how gallery-goers of the time found his Cubist depictions of Dora Maar shocking, asking “How is it possible for an artist to look at a model and see her in this way?” . What these viewers missed is that Picasso intended to see her “in this way” – he was using his unique visual language to convey something far beyond her outward appearance. The incredulity of those early viewers (“the faces are twisted… noses appear like snouts!”) is echoed whenever today’s audiences encounter a portrait that defies the conventions they expect. In essence, they are speaking a different visual language. As Picasso himself once quipped, for someone who doesn’t understand Cubism, looking at a Cubist portrait is like a person who cannot read English staring at an English book – the deficiency lies in the viewer’s familiarity with the language, not in the artwork’s validity.

Another misunderstanding is the assumption that interpretive or abstract portraiture is somehow a fallback for artists who “can’t do realism.” This is a pervasive trope: the idea that if a portrait has wonky proportions or fantastical colors, it must be because the artist isn’t skilled enough to do it “right.” In reality, the great interpretive portraitists were extremely skilled in traditional rendering – their deviation from realism was a choice, not a shortcoming. Recall that Picasso could draw and paint naturalistically in his youth, and even in his later years he would occasionally prove it, almost cheekily, to silence doubters. Similarly, Egon Schiele underwent rigorous academic training; he knew the rules he was breaking. And as discussed, Lucian Freud devoted his life to mastering representation, only to push it to expressive extremes. Far from lacking ability, these artists possessed such fluency in realism that they could bend and play with it at will. A psychological study of Francis Bacon’s work explicitly refutes the notion that his grotesquely distorted faces were a sign of incompetence: the distortion was “clearly deliberate. It is not from lack of artistic ability that features were distorted, rather it was a calculated decision.” In contemporary practice, too, one finds that artists who pursue interpretive portraiture often do so after mastering foundational skills. They choose to simplify, exaggerate, or alter the image because it serves their expressive purpose – not because they couldn’t produce a tight likeness if they wanted. This creative freedom sometimes meets resistance from viewers conditioned to admire hyperrealism. There’s no denying that a photorealistic pencil drawing garners quick praise on social media for its “wow, it looks like a photo!” factor. Technical virtuosity is indeed impressive. However, the value of a portrait is not measured solely by its technique; it’s also measured by its impact, meaning, and originality. An interpretive portrait might not fool the eye into thinking it’s a photo – but it can move the heart or intrigue the mind in ways a photo-realistic image might not. The misunderstanding, then, is in thinking of interpretive art as inferior or “incorrect.” In truth, it is simply operating with different aims. Once viewers attune to those aims (emotion, narrative, commentary, insight), they often find interpretive portraits far more engaging and memorable than any straightforward copy of reality.

Conclusion

Interpretive portraiture, as we’ve seen, is far more than an idiosyncratic niche of art – it is a vital mode of expression that continues to matter in our image-saturated world. In an age when cameras are everywhere and realistic images can be produced with a click, one might ask: why do we need portraits that diverge from what we see? The answer lies in what art uniquely offers. Art is not bound by the literal; it can condense time, emotion, and idea into a single image in ways a photograph cannot. An interpretive portrait distills a person’s presence as experienced by the artist (and ultimately by viewers) – it can comment on the subject’s inner life, societal role, or the artist’s relationship with the subject. This makes interpretive portraits especially powerful in conveying aspects of humanity that a straightforward likeness might leave untouched. They invite us as viewers to engage actively: to interpret the symbols and stylizations, and in doing so, to reflect on who the subject is and what they mean to us. Such art can create an emotional or intellectual resonance that outlasts the initial act of recognition.

Equally important, interpretive portraiture asserts the value of individual perspective in an era of mechanical reproduction. It reminds us that seeing is not a neutral act – two people will see the same individual differently. The artist’s distortion or emphasis teaches us something about the subject and about the artist’s own viewpoint, creating a dialogue across time and space. This enriches our experience of art and portraiture. A gallery visitor standing before a Picasso or a Kollwitz is invited to step into the artist’s shoes for a moment, to see another human being refracted through a different mind and heart. That exercise can foster empathy and insight. It can challenge our assumptions of what a person “should” look like, or what stories a portrait can tell. In short, interpretive portraiture matters because it expands the possibilities of portraiture from mere representation to revelation. It aligns with the profound idea that art, at its best, reveals truths under the surface of appearances. The face we present to the world is often a mask of convention – interpretive art peels that away. By embracing creative “lies” to convey truth, it delivers a more nuanced understanding of identity and experience. As Picasso put it, “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.” The painters of interpretive portraits take this to heart. They deliberately bend truth (visually speaking) in order to illuminate the multifaceted truth of a person’s existence. And that, ultimately, is why interpretive portraiture matters more than one might think – it transforms a portrait from a mere record of outward appearance into a powerful exploration of meaning, one that resonates on personal, cultural, and even philosophical levels.