Case Study: Analysis of Botticelli Primavera

- Yana Evans

- Aug 16, 2025

- 10 min read

CONTENTS:

No work better illustrates the layered nature of Renaissance art than Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera (“Spring”). This celebrated panel – tempera grassa on wood, about two by three meters – has become an emblem of early Renaissance elegance, myth, and humanist philosophy. At a glance, it charms as a scene of mythological figures in a sun-dappled orange grove. But, as with all masterpieces of this era, the more closely you look through the lenses we explored in Part I – materials, patronage, technique, iconography, and historical context – the more it reveals itself as a dense, poetic statement of its time.

Overview and Significance

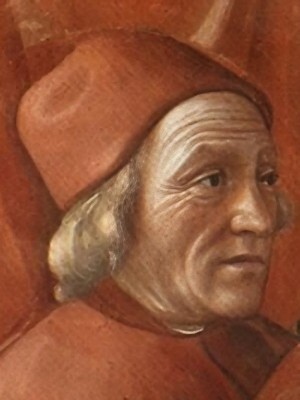

Painted in the early 1480s, Primavera opens like a stage curtain onto a lush, perpetual spring. Beneath a bower of orange and laurel trees, the ground is scattered with a thousand tiny blossoms. Nine figures from classical myth stand as if in a choreographed procession, their forms linked by rhythm and gesture. At the centre, Venus – calm, self-possessed – presides over the garden, framed by dark foliage. Above her, Cupid hovers, blindfolded, his bow drawn toward the left, the arrow’s destination a mystery. To her left, the Three Graces spin in a light, harmonious dance, their translucent gowns catching the light like ripples of silk. At the far edge, Mercury, in winged sandals and crested helmet, extends his caduceus to dispel a lingering wisp of cloud. On the right, the air stirs: Zephyrus, god of the west wind, sweeps in, seizing the nymph Chloris. From her parted lips spill tiny flowers, for in the next breath she will emerge as Flora, radiant in a gown patterned with spring’s abundance, scattering roses into the grass.

Our main actors:

Materials & Technique

Botticelli used tempera grassa – pigment bound with egg yolk and a little oil – on a wooden panel, a medium that allowed for his signature precision of line. Every contour of hair, fold of cloth, and edge of petal is rendered with exquisite clarity. Now softened by time, the colours originally would have been more luminous; yet even after five centuries, the matte, pastel quality of tempera lends the painting its dreamlike stillness.

The background is a dense tapestry of vegetation, painted with an almost scientific exactitude. Modern scholars have identified over 130 plant species and nearly 200 individual flowers, including violets, irises, cornflowers, and periwinkles – each painted with botanical accuracy. This was no mere decoration: it reflects a Renaissance fascination with the natural world, fostered by the revival of ancient herbals such as Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, circulating in Florence’s humanist circles. The laurel trees echo both the name of Lorenzo (Lauro) de’ Medici and the poetic triumph of Apollo, while the oranges – golden spheres glowing among the leaves – recall both the Garden of the Hesperides and the Medici coat of arms, whose palle were often likened to citrus.

Patronage & Context

Most scholars connect Primavera to the 1482 marriage of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, cousin of Lorenzo “il Magnifico,” to Semiramide Appiani of Piombino. The Appiani ruled a small but strategically vital coastal principality in the Tyrrhenian Sea, controlling the port of Piombino and the island of Elba. Their alliances stretched to the Kingdom of Naples and other Italian powers, so this marriage brought Florence closer to key maritime routes and strengthened Medici diplomatic networks. A panel celebrating fertility, harmony, and abundance would have been a fitting nuptial gift, underscoring the hope for prosperity in both family and state. Inventories record the painting in Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco’s townhouse above a lettuccio (a carved daybed or chest), suggesting it decorated a private, domestic space rather than a public hall.

This was a Florence still under the cultural leadership of Lorenzo il Magnifico, only a few years after the Medici survived the 1478 Pazzi Conspiracy. Peace and prosperity in the 1480s allowed Lorenzo to consolidate power not only politically but also through art and spectacle. In this climate, mythological paintings for private palaces flourished – works that blended classical beauty with coded messages about virtue, love, and the patron’s cultivated identity.

The imagery in Primavera likely drew upon the counsel of poets and philosophers in Lorenzo’s circle, notably Angelo Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino.

Ficino was the leading voice of Florentine Neoplatonism – a revival of Plato’s philosophy that sought to harmonise classical thought with Christianity. In Ficino’s view, beauty in the material world was a reflection of divine perfection, and contemplating it could raise the soul toward God. He distinguished between Venus Vulgaris (earthly, physical love) and Venus Coelestis (divine, spiritual love), urging a balance between passion and virtue. In Botticelli’s Venus Humanitas, modestly dressed and poised between the sensual drama of Zephyrus and the rational calm of Mercury, we see this synthesis vividly embodied.

Analysis of Iconography & Symbolism in Botticelli Primavera

The right-hand drama of Zephyrus, Chloris, and Flora comes from Ovid’s Fasti (V. 195–212). In the poet’s telling, Zephyrus seizes the nymph, but “as she speaks, roses fall from her lips,” and she becomes Flora, goddess of flowers, who now scatters them freely. Botticelli visualises this transformation with a stroke of genius: tiny blossoms stream from Chloris’s mouth as Zephyrus envelops her, while beside them Flora steps forward, serene, with a gown patterned in over forty species of flowers. For a contemporary viewer – especially a bride – this metamorphosis could symbolise the transition from maiden to fruitful wife.

Venus at the centre presides over this garden, her right hand raised in a gesture of welcome or benediction. Above her, Cupid’s blindfold speaks to love’s unpredictability, his arrow aimed at the central Grace. These Three Graces – Pleasure, Chastity, and Beauty, as Edgar Wind identified – dance in a ring of giving, receiving, and returning love, a harmony that Renaissance Neoplatonists saw as the ideal state. The coy glance of the central Grace toward Mercury at the far left sets up a subtle romantic subplot: love (Cupid), having touched chastity (central Grace), moves toward reason (Mercury).

Mercury himself, clad in red and equipped with sword and caduceus, turns away from the scene, dispersing the final clouds of winter. In Virgil and other classical authors, Mercury is the guide and guardian; here, he may symbolise the intellect that protects the soul from base desire, completing Ficino’s ascent from sensual love to divine contemplation.

Every plant, gesture, and object carries weight. Violets and periwinkles underfoot signified love and fidelity; myrtle behind Venus was sacred to her; laurel stood for poetic triumph; and the orange grove – besides its Medicean overtones – evoked an eternal spring. Even the arrangement of figures in a shallow frieze, “pearls on a string,” echoes both ancient relief sculpture and the choreographed processions (Trionfi) that Lorenzo de’ Medici staged for civic festivals, where costumed allegories of the seasons and gods paraded through Florence.

Glossary of Figures in Primavera

Venus – Roman goddess of love, beauty, and fertility.

Cupid – Son of Venus, god of desire and attraction, often depicted as a winged boy with a bow.

Zephyrus – God of the west wind, associated with the arrival of spring.

Chloris – A nymph in Roman myth, transformed into Flora.

Flora – Goddess of flowers and springtime.

Mercury – Messenger god, also protector and guide, associated with commerce, eloquence, and boundaries.

Three Graces – Goddesses representing charm, beauty, and creativity (variously named Pleasure, Chastity, and Beauty in Renaissance interpretation).

Stylistic Choices & Composition

Botticelli resists the deep, linear perspective favoured by many of his contemporaries, instead arranging his figures in a shallow, tapestry-like meadow. This deliberate flatness heightens the sense that we are watching a staged performance – a tableau vivant, or “living picture.” In Renaissance courts, a tableau vivant was a popular form of entertainment: costumed actors would stand motionless in arranged poses, often recreating scenes from classical myth or history, framed by elaborate sets. Guests would view these living pictures much like a painting, admiring the artistry of costume, gesture, and symbolism.

Florence under Lorenzo de’ Medici excelled in such spectacles. During civic festivals and wedding celebrations, the city streets filled with Trionfi – processional pageants featuring allegorical floats, musicians, and actors frozen in carefully choreographed poses. Botticelli’s scene echoes this culture: his mythological figures stand like costumed performers, poised at the front of a shallow stage, each role instantly recognisable to an educated audience.

This theatricality is matched by his stylistic blend. The flowing lines, weightless draperies, and elongated forms recall the elegance of late Gothic court art, while the naturalistic faces, botanical accuracy, and precise anatomy draw from Renaissance humanism. In Botticelli’s hands, these two traditions merge, producing a composition that feels timeless – neither fully anchored in medieval pageantry nor entirely in the rational space of the High Renaissance. Instead, Primavera exists in an eternal spring, a visual performance that, like the festivals that inspired it, celebrates beauty, harmony, and the union of art and life.

Seeing Primavera Today

Today, Primavera hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Its journey from a private Medici palace to a public museum mirrors Botticelli’s own curious afterlife. In his own time, Botticelli was celebrated, especially in the 1480s and 1490s, as a leading Florentine painter. But tastes changed swiftly in the early 16th century. The rise of High Renaissance ideals under Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo favoured monumental compositions, robust anatomy, and complex spatial illusion – qualities quite different from Botticelli’s linear elegance and poetic symbolism.

Botticelli’s later years also coincided with the turbulent era of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, whose sermons against worldly vanities may have influenced the artist’s move toward more austere religious imagery. By the time of his death in 1510, his mythological works like Primavera were seen as quaintly old-fashioned. For the next three centuries, Botticelli’s name was preserved mostly in inventories; Primavera itself remained in Medici hands, then passed quietly into the Uffizi’s collection in the 19th century without attracting much notice.

His revival began in the mid-1800s, when a wave of interest in “early” Renaissance art swept through Britain. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones – admired the purity of line, decorative rhythm, and lyrical mood in Botticelli’s work, which matched their own ideals of beauty before Raphael’s “perfection” changed the course of art.

In 1870, art historian and critic Walter Pater praised Botticelli in his "Studies in the History of the Renaissance", describing the painter’s “peculiar charm” and “melancholy grace.” This sparked further scholarly and collector interest. By the late 19th century, Botticelli had become a symbol of refined, poetic vision, influencing not just painters but poets and designers in the Aesthetic Movement.

Standing before Primavera today, with its softened greens and gently faded blossoms, we see not only a masterpiece of 15th-century Florence but also a survivor of changing fashions – a work once forgotten, now treasured as one of the defining images of the Renaissance. Every curl of hair, every embroidered flower still bears the precision of Botticelli’s hand, inviting us to imagine the newlyweds of 1482 gazing on it as a visual hymn to love and renewal.

Conclusion – Art as a Historical Document

Renaissance art endures not only for its beauty but because it is a record of its age – a visual document of values, beliefs, fashions, and ideas. In Primavera, we see 1480s Florence distilled into a single panel: classical mythology reimagined through humanist philosophy, Medici politics woven into a garden of eternal spring, and the technical mastery of a workshop steeped in both tradition and innovation.

When we learn to see art with informed eyes, a painting becomes more than an image; it becomes a conversation across time. The choice of tempera grassa, the Medici oranges, the laurel for poetic triumph – each detail speaks of a world where materials were tied to trade routes, symbols to shared cultural codes, and composition to philosophical ideals.

This is why art is evidence. It tells us how people once saw their world and what they held dear. Just as Primavera encodes the optimism of a Medici wedding and the intellectual climate of Lorenzo il Magnifico’s court, every classical artwork carries its own set of clues: the ambitions of its patron, the hand of its maker, the influence of distant styles brought home by merchants or diplomats.

Standing before such a work is an act of time travel. You can picture Botticelli in his workshop, grinding pigments, or Marsilio Ficino discussing the virtues of Venus Humanitas. You can imagine the first viewers – perhaps the bride herself – seeing Flora scatter her roses and recognising both the myth and the message. The painting has survived plagues, wars, and centuries of changing taste, yet it still offers us an unbroken thread back to that moment.

As the Renaissance itself taught: Ars longa, vita brevis – art is long, life is short. These masterpieces have outlasted their makers and will outlast us, but in our brief span we can meet them halfway, letting them teach us about history, creativity, and the heights of human expression. Knowing the story behind a work does not dispel its magic; it makes that magic bloom brighter.

In the end, art appreciation is about connection – bridging the gap between looking and seeing, between our world and the world of the artwork. When you truly see a Renaissance painting, you share, for a moment, an understanding with those who stood before it centuries ago. That is one of art’s greatest gifts: it collapses time.

Practical Guide: How to Look at Classical Art Today

The joy of classical art is in the slow discovery – the moment when a scene stops being a flat image and begins to reveal the world it came from. Here’s a framework, drawn from the way we made an analysis of Botticelli’s Primavera, that you can take into any museum.

Take Your Time

Stand with the work long enough for your eyes to travel across it. Classical paintings were made to reward patience. Like the shifting focus in Primavera, where the drama of Zephyrus and Chloris competes gently with the calm of Venus, details reveal themselves in layers.

Orient Yourself in the Scene

Identify the main figures and how they’re arranged. Ask: is this a narrative moment, a procession, a symbolic tableau? In Renaissance art, placement is never random. Venus in the centre of Primavera anchors every other movement in the scene.

Look for Symbols and Attributes

Classical painters loved visual shorthand – a laurel crown for poetry, a bow for Cupid, a caduceus for Mercury. These attributes link to myths, virtues, and ideas that deepen the meaning. Recognising them turns the painting into a readable text.

Consider the Historical Setting

Think about when and why the work was made. A mythological scene painted for a Medici wedding has different intentions than the same myth painted for a public hall. Context can explain choices in costume, setting, and even the mood of the piece.

Notice the Technique

Step closer. Is the surface matte, like tempera, or rich and layered, like oil? Are the lines crisp or blended? The precision of Botticelli’s tempera grassa is part of Primavera’s delicate, tapestry-like effect – very different from the oil-saturated works in Venice at the same time.

Watch the Figures for Clues to Emotion

Body language in classical art can be subtle: a glance, a tilt of the head, a hand’s position. The coy look from the central Grace toward Mercury in Primavera adds a whole romantic subplot invisible to a casual glance.

Treat It as a Time Capsule

Look at it as both art and evidence. The costumes, plants, architecture – all tell you something about the world that produced them. A dress patterned with specific flowers might echo the textiles of the time, just as the orange grove in Primavera nods to the Medici’s own emblem.

The same patience, curiosity, and attention to detail that reveal the layers of Primavera will unlock countless other works from the classical tradition. Every careful look is a step closer to the world that produced the art – its patrons, its makers, its ideas. And that is where the real reward lies: when a painting stops being an object on a wall and becomes a living link to history.