Camomile Through Time: The History and Symbolism of a Cultural Motif

- Yana Evans

- Aug 8, 2025

- 10 min read

CONTENTS:

More than just a soothing tea, the camomile flower carries a legacy that spans continents and centuries. Delicate white petals and a golden heart give it an unassuming look, yet camomile has quietly influenced medicine, art, and folklore around the world. In its gentle aroma – often likened to apples on a summer breeze – lie echoes of ancient rituals and grandmother’s remedies. Once sacred to sun gods and strewed on cottage floors for luck, this humble blossom has been a symbol of resilience and comfort across cultures. We find camomile celebrated in poetry and painting, prescribed by healers from Egypt to England, and even honored today as the beloved national flower of Russia. From temple incense to bedtime tea, the story of camomile is a fragrant thread woven through human history, uniting the mundane with the mystical in a timeless cultural tapestry.

Origins and Discovery: Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The camomile plant (genus Matricaria or Chamaemelum) is a member of the daisy family, its name derived from the Greek chamaimelon, meaning “earth-apple,” for the applelike scent of its blossoms. Botanically, camomile is a small herb with feathery leaves and cheerful white rays around a yellow disc – a form so familiar that ancient scholars barely found it worth describing. As the 17th-century herbalist Nicholas Culpeper joked, camomile “is so well known everywhere, that it is but lost time and labour to describe it”. Two primary varieties came to be revered: German camomile (Matricaria chamomilla, an annual) and Roman camomile (Chamaemelum nobile, a perennial). Fittingly, the Latin genus Matricaria means “womb” – a nod to the herb’s longtime use in women’s health.

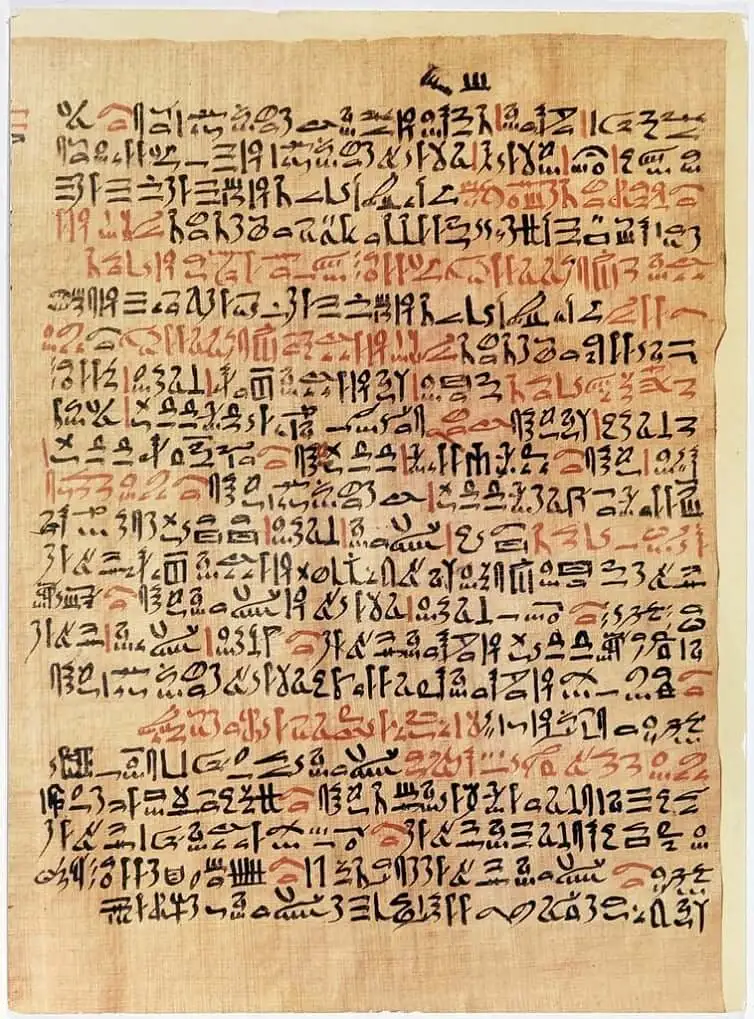

Camomile’s recorded history reaches deep into antiquity. In ancient Egypt, physicians documented its powers on scrolls like the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE). The Egyptians dedicated camomile to their sun god Ra, perhaps seeing in its golden-centered blooms a reflection of the sun. They prized it as a universal remedy, from calming fevers (even malaria) to perfuming cosmetics. High-ranking Egyptians used camomile in skincare and beauty treatments, and notably, camomile oils were used in mummification, an aromatic tribute to ensure safe passage to the afterlife.

Classical Greeks and Romans likewise embraced camomile. Greek physicians in the age of Hippocrates (5th century BCE) recommended camomile infusions to reduce fevers and female ailments. The great naturalists Theophrastus and Dioscorides described its appearance and “apple” fragrance, and Dioscorides noted how camomile’s gentle warmth could “thin” the excess humors, making it a remedy for urinary, digestive, and gynecological complaints. Roman healers catalogued camomile’s uses for everything from inducing menstruation to treating kidney stones. The Romans so esteemed this flower that they consecrated it to their gods and made it a staple of daily life – it was strewn on floors as a natural air freshener, infused in communal baths, and sipped as a healing tisane. By the 1st century CE, Pliny the Elder could list camomile among the most celebrated herbs of the empire. In these early civilizations, camomile was more than a plant – it was a gift from the divine, a modest weed elevated to a sacred healer.

Spreading Across Continents: Monks, Traders, and Conquerors

From its Mediterranean cradle, camomile ventured far and wide, carried by legions, traders, and green-thumbed monks. The Romans likely introduced camomile to the far reaches of Europe as they marched – its seeds finding home in British meadows and Gallic fields. After the Roman Empire, it was the monasteries of medieval Europe that kept camomile’s legacy alive.

In the 9th century, Emperor Charlemagne’s famous decree Capitulare de villis listed camomile among the essential herbs to be grown in every imperial garden. Monastic healers duly cultivated camomile in their physic gardens, alongside sage and betony, to treat the sick. An Old English herbal recorded camomile for headaches and “windy” stomachs, and indeed Anglo-Saxon leechbooks praised this herb.

Camomile even entered Anglo-Saxon lore: a medieval legend held that the god Woden (Odin) gave nine sacred herbs to mankind – camomile (called maythen in Old English) among them – to ward off evil and illness. Such tales underscored camomile’s status as a panacea in early northern Europe.

As trade routes opened, knowledge of camomile spread to the Middle East and beyond. Persian polymath Avicenna included camomile in his Canon of Medicine (1025 CE), recommending it for headaches, jaundice, and women’s ailments among other uses. In the Arab world, camomile’s cooling qualities were blended into Islamic medicine’s rich herbal repertoire, often aligning with earlier Greco-Roman findings. Through the Islamic Golden Age, camomile’s fame traveled along with sugar, spices, and texts, eventually reaching the Indian subcontinent and Asia. By the time of the Renaissance, camomile was firmly ensconced in herbals from Baghdad to London. Herbalists like Germany’s Hieronymus Bock and England’s John Gerard grew it in their gardens and extolled its virtues in print.

Camomile crossed the Atlantic with European colonists in the Age of Exploration. Settlers brought dried camomile and seeds to the Americas in the 1600s, ensuring they had their familiar “cure-all” on new soil. Indigenous peoples of North America soon learned its properties as well, adding it to their own pharmacopoeias. By the Revolutionary War era, camomile was so common in the Thirteen Colonies that patriot soldiers foraging for medicine turned to wild camomile when supplies ran low. Indeed, accounts from the American Revolution note that soldiers carried camomile in their kits, alongside mint and yarrow, to treat camp maladies like dysentery, wounds, and fatigue. Colonial households grew camomile in kitchen gardens for teas and tonics, especially after the Boston Tea Party made imported tea scarce – camomile became one of the favored “Liberty teas” brewed by American patriots. From Europe to Asia, Africa to the New World, camomile journeyed as a cosmopolitan herb, adapting to local gardens and healing traditions everywhere. It flourished by roadways and field edges, naturalizing on every continent where humans tended it. By the 19th century, camomile truly belonged to the world, a ubiquitous traveling companion in the story of global herbal medicine.

Symbolism and Meaning: Patience, Purity, and Protection

Beyond its medicinal virtues, camomile blooms with symbolic meaning in cultures around the world. Perhaps its most universal association is with resilience in adversity. A trampled camomile plant, rather than withering, famously releases more of its sweet fragrance and often springs back stronger. In the Victorian language of flowers, camomile came to signify “energy in adversity” or “patience in adversity”. Gifting someone a camomile blossom was a way to say, “Stay strong; have patience through difficulties.” The flower’s hardiness – thriving on dry, poor soils and surviving footfall – made it a natural emblem of endurance and humility in European art and literature.

Camomile also symbolizes good fortune and prosperity in folklore. In many Old World traditions, it was considered a lucky flower. Medieval folk carried camomile in their pockets or made garlands of it hoping to attract success and love. To gamblers, washing one’s hands in camomile tea was a charm for winning streaks. Camomile was scattered around homes to ward off evil and invite positive vibes – echoing its use as a strewing herb on cottage floors to protect against disease and bad spirits. In some places, camomile was linked to religious observances: for instance, in parts of Europe wreaths of camomile were hung on St. John’s Day (Midsummer) to guard houses from lightning and storms. Large bonfires on that night would have camomile tossed in, the aromatic smoke believed to carry protective magic for the coming year. In Welsh tradition, camomile was even planted on graves to ensure the peaceful rest of souls – its gentle presence a symbol of eternal peace and innocence.

Wartime folklore also found a place for camomile. A poignant German legend avers that camomile flowers sprang from the blood or souls of soldiers who fell in battle under a curse, their spirits finding repose in the flower’s gentle countenance. Whether to symbolize the tragedy of war or the hope of healing afterward, camomile was seen as a flower of remembrance and solace. Even during World War II, British families cultivated camomile when imported tea was rationed – a small comfort in hardship, and later a nostalgic symbol of wartime endurance.

In summary, camomile’s symbolism is rich and uplifting: it stands for resilience, patience, good fortune, peace, and modest virtue. A simple camomile lawn in a garden invites contemplation on the strength of the humble. As one 19th-century herbal rhyme put it: “The aromatic fragrance gives no hint of its bitterness of taste… The more it is trodden, the more it will spread.” In that duality – sweet appearance, bitter medicine – people have seen a metaphor for life’s trials and the quiet strength to overcome them.

In Literature, Art, and Love Stories: A Muse in Miniature

Camomile’s gentle presence has quietly infused itself into literature, poetry, and art through the ages, often as a symbol of comfort or perseverance. William Shakespeare gave camomile one of its most famous literary mentions. In Henry IV, Part 1, the roguish Falstaff wryly tells Prince Hal: “For though the camomile, the more it is trodden on, the faster it grows, yet youth, the more it is wasted, the sooner it wears.” Shakespeare used the herb as a metaphor for resilience – camomile thrives underfoot, unlike human youth which fades with misuse. His audiences would have smiled at the reference, as camomile lawns were actually common in Elizabethan gardens; people knew that walking on camomile released its apple scent and did it no harm. This Shakespearean image of the lowly camomile outlasting adversity has reverberated in writings ever since.

Romantic poets also found meaning in herbs and flowers, and while camomile did not star as prominently as the rose or lily, it made its appearances as a symbol of rustic peace. John Keats, who trained as an apothecary, would have been intimately familiar with camomile’s fragrance from his studies – one can imagine the young poet brewing camomile to soothe his own stresses. In one tender letter, Keats prescribes “a cup of camomile” for an anxious friend, linking it to calm and rest (a quiet footnote to his more famous nightingales and autumn odes). Similarly, 19th-century American poet Walt Whitman references wild camomile (pineapple weed) dotting the gritty streets of Manhattan in Specimen Days, admiring how these resilient flowers scented the urban air with nature’s balm. Camomile thus finds its way into the margins of poetry as a friend of the weary – a plant that offers calm in a chaotic world.

In the realm of folktales and love stories, camomile often plays a gentle hero. A Ukrainian folk legend tells of a young mother desperate to cure her ailing son; an old healer directs her to a meadow of wild camomiles. She brews their blossoms into a tea which miraculously restores the boy’s health. Ever since, Ukrainians see camomile as a symbol of goodness and health, and the flower is beloved in Ukrainian songs and embroidery as an emblem of motherly love and well-being. In Polish folk medicine too, camomile was an ingredient in love potions and bridal wreaths, signifying devotion and fertility. Across Slavic traditions, girls would include camomile in the wreaths they cast into rivers on midsummer’s eve – its presence believed to enhance their chances of seeing visions of a future love. And of course, the simple act of plucking camomile (daisy) petals – “He loves me, he loves me not” – is an age-old form of divination in matters of the heart, a charming game of chance that appears in European lore by the 18th century and persists to this day.

Visual artists have also been inspired by camomile’s unpretentious charm. In the Dutch Golden Age, painters like Rachel Ruysch and Jan Brueghel the Elder, famed for their lush still-life bouquets, often included a stray camomile or two among the roses, tulips, and peonies.

These tiny white daisies in the arrangement served a dual purpose: aesthetically, they offered a splash of wild simplicity, and symbolically, they introduced a note of humility and healing amid the opulence. An inventory of Ruysch’s 1720 painting Flowers in a Vase lists “camomile” alongside poppies and marigolds, suggesting she deliberately painted recognizable medicinal flowers into her compositions (perhaps a nod to her botanist father’s influence).

Later, in the 19th century, Vincent van Gogh created a tender still-life titled Poppies and Chamomile (1890), juxtaposing fiery red poppies with the meek camomiles – a contrast of passionate and calm. The camomiles in Van Gogh’s work, with their sunny faces, seem to diffuse a sense of tranquility across the canvas, balancing the more dramatic blooms. Through such artworks, camomile left an understated imprint on art history as a symbol of rustic purity, peace, and the healing power of nature.

Even children’s literature has embraced camomile. Beatrix Potter’s classic The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) famously concludes with poor Peter tucked into bed and given a dose of camomile tea by his mother to calm his upset tummy after his misadventures in Mr. McGregor’s garden. Potter, a keen herbalist herself, chose camomile as the remedy to highlight its age-old role as a gentle comfort for children. The scene is more than a plot detail – it’s a cultural wink that any reader, recalling a parent or grandparent who made them camomile tea for bellyaches or nerves, can instantly appreciate.

From the pens of Shakespeare to the paintbrushes of Van Gogh to the bedtime stories of our childhoods, camomile has been a quiet muse, symbolizing comfort, resilience, and natural goodness whenever it appears.

Conclusion – The Timeless Charm in History and Symbolism of Camomile

Across the grand sweep of history, from the temples of pharaohs to the cottages of villagers to the laboratories of scientists, the camomile flower has been a quiet constant. Its historical, cultural, and artistic significance is a reminder that sometimes the smallest things carry the deepest meanings. Camomile teaches patience by example: trodden underfoot, it grows back stronger; brewed in a cup, it gently dispels our troubles. Culturally, it has connected people through shared rituals – the simple act of sipping camomile tea is one our ancestors from millennia past would understand and appreciate. It has inspired healers to care for others, artists to find beauty in simplicity, and poets to find hope in hardship.

In our hectic modern world, the poetic legacy of camomile endures every time someone pauses, breathes in its sweet scent, and feels a sense of calm. We are, in a way, continuing the human-love affair with this little flower that has lasted for ages. As you next cradle a warm mug of camomile or notice its daisy-like blooms along a footpath, consider the rich tapestry of stories behind it – the ancient sun worshippers, the wise herbalists, the storytellers and painters who all celebrated this bloom. The camomile is indeed more than a tea ingredient; it is a symbol of timeless comfort and resilience, a tiny flower with a mighty cultural footprint. In camomile’s gentle petals lies a universal message: find strength in gentleness, and peace in the simplest of nature’s gifts.