Yesenin in Context: Play Garmonika Poem – Original English Translation and Literary Analysis

- Yana Evans

- 1 day ago

- 14 min read

Updated: 4 hours ago

Content and intro:

Special note: I couldn’t wait for help and tried to voice my translation with AI myself. I just couldn’t bear waiting any longer. I wanted so badly to hear in real life what had only existed in my head, to see whether my imagination matched reality. I’m not a musician (I don't even listen to music that much), and I’m not really good with AI either. But I’m so happy with the teaser I ended up with. My translation works. It actually works. If anyone feels like refining or developing the composition further, I’d be glad. Share a link to what you come up with. Special thanks if you credit me as the author of the translation, and the hooligan Yesenin. UPDATE: Basically, I spent a bunch of time poking at buttons, fiddling with all kinds of levers, and reading a ton about different ways to split vocals, plus figuring out music genres and styles (yeah, I didn’t know any of this before). And… voilà. A pretty solid English adaptation of the whole track. I hope you can get a little taste of Russian culture and really feel it! With that, I’ve finally closed this little chapter for myself haha.

Сыпь, гармоника! Скука… Скука…

Гармонист пальцы льет волной.

Пей со мною, паршивая сука.

Пей со мной.

Излюбили тебя, измызгали,

Невтерпёж!

Что ж ты смотришь так синими брызгами?

Или в морду хошь?

В огород бы тебя, на чучело,

Пугать ворон.

До печенок меня замучила

Со всех сторон.

Сыпь, гармоника! Сыпь, моя частая!

Пей, выдра! Пей!

Мне бы лучше вон ту, сисястую,

Она глупей.

Я средь женщин тебя не первую,

Немало вас.

Но с такой вот, как ты, со стервою

Лишь в первый раз.

Чем больнее, тем звонче

То здесь, то там.

Я с собой не покончу.

Иди к чертям.

К вашей своре собачей

Пора простыть.

Дорогая… я плачу…

Прости… Прости…

1923 г.

Play, garmonika! Blear… Blear…

The player’s fingers ran in waves

Drink with me, slatternly twat

Drink with me.

They’ve loved you, besmirched,

Used you raw.

What’s with those blue pools of yours?

’Ave a crack?

Toss you in t’croft, a tattie-bogle

to scare the crows.

You’ve worn me out to the core

Bled me dry

Play garmonika! Play, my restless one!

Drink, tart, drink!

I’d rather that one, the bosomy

She ain’t that bright

Of all my women... ain’t the first.

A fair few.

But with someone like you, a nasty shrew,

First go for me.

Hurt more, kicks off

From hole to hole

I ain’t doing myself in

Off to hell.

To your filthy pack

Best go cold.

My dear… I’m crying…

Forgive me… forgive…

S. Yesenin, 1923; translation: Y. Evans, 2026

Comments on the Translation

In fact, I could not find a high-quality translation of Yesenin’s poem “Play, Garmonika”. Everything I came across looked like a direct Google translation: the words were there, but the meaning was lost. Idiomatic expressions, emotional nuances, and the depth of the author’s experience all disappeared. For an English-speaking reader, this turned into an empty phrase, stripped of soul. Even the word “сыпь” would have a strange literal translation, though in context it actually refers to actively playing a musical instrument.

So, I decided to create my own translation, one that preserves the emotional rhythm, conveys the author’s inner state, and makes it at least partly understandable to an English-speaking audience. This is not just a translation of words; it’s an attempt to convey the feelings Yesenin embedded in the poem and the pain he hid behind the outward noise of the world.

Some notes on the translation: for example, the musician in the poem plays a Russian instrument, the garmonika, which in English is usually called either a bayan or, unpleasantly, a squeezebox. In English, the word “harmonica” is associated exclusively with the small mouth harmonica, which has nothing to do with the work. I kept the word “garmonika” deliberately, because using bayan or squeezebox would sound simply terrible to the ear.

Yesenin uses the metaphor of virtuosity on a keyboard instrument, where the fingers “flow” like water. It’s the stream of fingers, the smoothness and mastery of execution that a Russian-speaking reader feels immediately.

Another example: the phrase “смотришь синими брызгами” (“you look with blue splashes”). In Russian, eyes are often compared to oceans, lakes, or splashes, especially if they are blue. A native speaker instantly understands this refers to eyes, not water, drinks, or food. Such idiomatic expressions are almost impossible to translate literally: the semantic and emotional depth is lost.

Many insults and curse words in the original I deliberately adapted. For example, the author calls a woman a “выдра” (otter). In Russian, this is a derogatory, insulting term for a woman, but in English, the word otter does not carry the same cultural meaning. A literal translation would raise questions: why an otter? Why is he suddenly drinking with an animal? Therefore, I chose analogous expressions to preserve both the rhythm and the emotional impact for an English-speaking reader. The same applies to many other words and phrases; their replacement allowed me to retain not only the rhythm but also the semantic depth of the work.

If you want a strictly literal translation, you can use Google Translate. You will understand the words, but expressions like “сидишь у меня в печенках” (you are sitting in my liver) will remain incomprehensible without cultural context. What matters is that in my translation I tried to convey not just words, but emotions, nuances, the author’s inner world, his pain and despair, which make the poem alive.

Commentary on the Work

Yesenin’s poem “Play, Garmonika”, written in 1923, two years before his death, reflects the author’s inner state. The main character is in a bar, drunk, interacting with a woman who is a prostitute. At first, he insults her and shows aggression. But then he admits that she has reached into his soul, calls her “dear,” and apologizes. This contrast between bravado and vulnerability shows the psychological conflict: he tries to escape the pain but cannot hide his true feelings.

His behavior is a classic defense mechanism. He drowns his suffering with alcohol, noise, and women. When there is a threat of revealing emotions, aggression surfaces. From an early age, Yesenin was surrounded by public attention. He was an actor, a theater performer, a star, and a crowd favorite. Social performance became dominant, while his true self and inner needs were partially inaccessible. This weakened his connection with the core of his personality and created a basis for deep depression. The mask had long become the primary form of existence for Yesenin, and most sadly, he likely did not even know what his true inner needs were. A closed circle of pain with seemingly no way out.

This poem is a cry for help; it reflects not just an episode in a bar but a deep psychological portrait of a person struggling with inner pain while living in an extremely public environment. Aggression followed by confession shows an attempt to maintain control over the inner world. Efforts to drown the pain through external means, constant performance, and masking of emotions create a tense dynamic. Two years later, this struggle led to a tragic outcome.

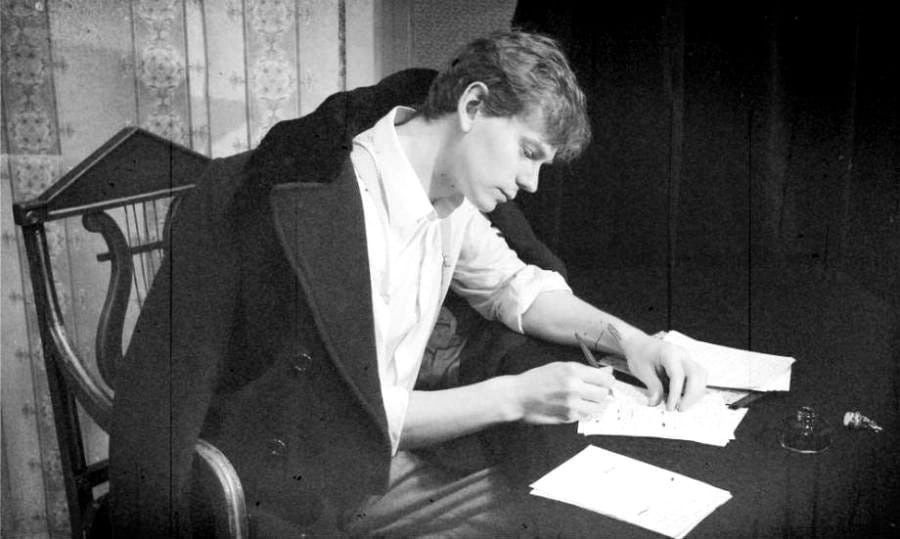

Sergei Yesenin was one of the brightest poets of the Silver Age. It must be understood that at that time poets and writers were like influencers and rock stars today. And here Sergei hit the jackpot: the looks of a sex symbol with golden curls and blue eyes, sometimes neat suits, a top hat, high collars, sometimes a peasant shirt, boots, rustic masculinity, and a sharp, cutting word. He answered all the demands of his contemporaries and truly became an idol of his time. Binge drinking, affairs, loud companies, prohibited substances and alcohol flowing like a river, decadence turned up to the maximum, and he was the main figure on the scene.

A turbulent young character and an era of great changes provided both many opportunities and many dangers. Carried away by “rebellion for the sake of rebellion,” in his youth he became fascinated with socialist ideas and revolutionary romanticism, because it was so fun, slogans, movement, resistance, going against the system and being different from everyone else. Unfortunately, the new Soviet authorities would not support him and would not be as lenient toward him as Imperial Russia had been.

After the revolution, his work was pushed into the background and hidden: too much personal content, too much truth and frankness, which did not fit well into the new ideology. Nevertheless, years later, in the sixties, his portrait, alongside Hemingway’s, often hung in the homes of the intelligentsia.

Formation of character

Yesenin was born in 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo in the Ryazan province, into a peasant family. His parents separated early: his father left to earn money in Moscow, his mother went to Ryazan. Sergei was raised from an early age by his grandfather and three uncles, whom he later called “mischievous and desperate.” He grew up rowdy and quarrelsome. His grandmother scolded him for his wild temperament, while his grandfather, on the contrary, defended him and said that this was exactly how character and manhood were formed. Despite this, he studied well and graduated from the village school with a commendation certificate – a straight-A student, in modern terms.

At fourteen he entered a teacher’s school, and at the same age began writing his first poems and dreaming of a career as a poet. It is important to understand that at that time poets and writers were like rock stars, influencers, and bloggers for our generation. So Sergei had a very clear goal – he wanted to become a star, and he realized this very early.

At seventeen, after finishing teacher’s school and already having experience with dramatic romances behind him (he was involved with two girls from his village at the same time), Yesenin decided to move to Moscow to his father. A big city meant more opportunities. With no connections or money, his first jobs were in a butcher shop, then a bookstore, and later he got work as a loader in the largest printing house in Moscow. There he was noticed for being well-read and was made assistant to a proofreader named Anna, with whom he soon began living and with whom he had his first son. Responsibility, of course, did not appeal to the young man, and he fled from pregnant Anna to Crimea. Naturally, the trip was short; a red thread through Yesenin’s whole life was that he never stayed anywhere and was constantly in motion.

At nineteen, in 1914, Sergei became a father for the first time. That same year the Russian Empire entered the First World War. Amid a wave of patriotism and enthusiasm, anti-government sentiments that had been growing since 1912 also did not subside. Russia existed in a dichotomy of public moods.

Path to popularity and lifestyle

In 1914 his poems began to be published under a pseudonym, and a year later he moved to Petersburg in search of fame, connections, and the literary environment.

Alexander Blok was the first to seriously support him.

Against the backdrop of rising patriotism, Yesenin with his “peasant Rus’” fit perfectly. He read poems in a deliberately rustic dialect, which the public liked. At nineteen his name already appeared in newspapers alongside Gumilev, Kuprin, and Blok. Crowds attended his evenings.

In 1916 he began performing on stage as a storyteller for court circles: instead of a tailcoat he wore a peasant shirt and boots, adding folk ditties and rough humor. The hall was his. He fully matched the expectations of his contemporaries. Later that year he traveled to frontline zones and wrote war poems. He read the poem “Rus’” in an infirmary before the Empress and the daughters of Nicholas II and, when she said “beautiful, but sad,” he answered: “Such is all of Russia.”

At twenty-one Sergei found himself at the height of fame; with a turbulent character and hot blood, intoxicated by success, he quickly began burning through life. Life until the wallet was completely empty, everything instantly spent in taverns. A year later, in 1917, the patriotic rise turned into anger toward the authorities. And this seemed like Yesenin’s natural habitat — chaos, fights, alcohol, revolution. Although he himself admitted that he truly felt no belonging to any revolution.

In 1919, at age twenty-three, Yesenin created and joined the “Imaginists” circle. These were no longer salons but taverns, performances, scandals, bohemia. Life was bright but destructive. Nothing seemed to change in the poet’s life except that he was now under surveillance. The Chekists did not like him: too famous, traveling too much, too free. Yesenin, without a second thought, went to the Caucasus, from where the Reds had only recently pushed out the Whites, then to Baku and Tiflis, where the Red authorities were barely present. What is this if not anti-revolutionary activity in the eyes of the Cheka and the new government? Upon returning to Moscow he was immediately detained and, after three weeks in custody, thirteen criminal cases were opened against him. For “offenses” committed back in Imperial Russia – brawls in bars, hooliganism. The revolution he had supported in a “peasant” way ended up slapping him in the face. In such moments one wants to say, “I told you so,” and look with sour disapproval.

What was happening in the country: since 1912 anti-government, social-communist sentiments were brewing; in 1914 (Yesenin was nineteen) Russia entered the First World War, and three years later the revolution took place (Yesenin was twenty-two) – a military coup, the murder of the imperial family. In a country weakened by wars, chaos and lawlessness reigned. A vacuum of legitimate power, power seized by uneducated, embittered, cruel marginals. All dissenters began to be shot, detained, tortured. All the unwanted were stripped of property and even basic human dignity. Power passed into the hands of the Chekists. Subjectively, for me, they were degenerate humans, inhuman. An uncomfortable truth, but the activity of the revolutionaries in Russia was financed by England using the personal funds of the Russian Crown that were appropriated after the murder of the entire imperial family and stored in an English bank. Historically, we know that all who stood behind and followed the revolution were people from poor and uneducated circles.

Relationships

What can be said about Sergei Yesenin’s relationships?

This is, of course, a subjective view. But it is easily confirmed by the recollections of contemporaries and people who knew him personally.

Yesenin’s first child appeared when he had barely turned eighteen, from Anna, the girl he worked with at the Moscow printing house. When he learned about the pregnancy, he simply disappeared. He left for Crimea, abandoning both Anna and the unborn child. Later he formally acknowledged the child but took almost no part in raising him.

And this was essentially his typical pattern.

All his feelings were short and flash-like: fast, bright, passionate. But never deep. Never long. No stability. Everything superficial, on nerves, on emotion.

After Anna there were dozens of affairs. Then a marriage to Zinaida Reich. Two children were born in this marriage. The picture becomes this: a young man of twenty-five already has three children.

But even with Zinaida he could not build solid relationships, and the scenario repeated almost exactly like with Anna. After the birth of the baby in 1920, just a few months later Yesenin fell in love with Isadora Duncan, a spark, a flash, a stormy affair, divorce, a new wedding.

Zinaida loved him truly, seriously, for the long term. But he was constantly pulled elsewhere. Toward noise, adventures, taverns, decadence. He was an inconsistent person. A social butterfly, a moth flying into the fire.

The same showed in friendship. One could see how deftly he used the people around him: colleagues, acquaintances, others’ goodwill. He took warmth, attention, support, but rarely gave anything back except his chaotic energy rushing like a tsunami. Many people, especially creative ones, found his theatricality, brightness, and openness attractive and calmly tolerated his negative traits, as if they were a side effect of genius.

Bunin, one of his colleagues and a star of the Silver Age, from the very beginning rather harshly called him a two-faced person.

Honestly, it gives the impression that deep down he was very lonely. Despite the crowds around him. According to contemporaries, he had almost no strong, time-tested friends. He easily made acquaintances, knew how to charm and start communication. But he didn’t know how to keep people close. As if his interest burned out quickly.

A beautiful life on the outside. And complete emptiness where people usually build a home and a family.

The decline of the star

In 1921 Yesenin met the American dancer Isadora Duncan, and less than a year later they exchanged vows. She didn’t know Russian, he didn’t know any languages besides Russian, but passion flared up and apparently communication happened through body language. After the wedding they went traveling through Europe, and the main stop was Berlin: clubs, luxury, Egyptian cigarettes, expensive perfume, champagne, Berlin decadence and chic. But there he turned out to be unnecessary to anyone. His fame had stayed at home. This angered him. Very much. Soon he began writing sharp, insulting letters about Europeans. A defense mechanism?

After Berlin, Isadora had a tour in America. The Berlin scenario repeated itself, only in grayer tones. Isadora had a busy tour schedule, she was a star breaking the boundaries of propriety with her daring dances, sold-out performances, paparazzi everywhere. Yesenin was unknown, unnecessary, a nameless companion to his wife. Moreover, the public perceived him as a “Bolshevik agitator”; he was forbidden to conduct any activity, all literature in Russian was confiscated, there was Prohibition in the country and he couldn’t drown his anger in alcohol, and he couldn’t even talk, everyone spoke English, which he did not know. This caused an even bigger crack in his relationship with Isadora.

After the American tour ended, Isadora announced the end of her career and returned with Sergei to Soviet Russia. Once he got back to the bottle, Yesenin began drinking even more, tried to get treatment and stay in hospitals, but constantly ran away and started again. His relationship with Duncan ended completely in 1923 on Sergei’s initiative, while the poet remained in a permanent drunken delirium.

His last wife was Sofya Tolstaya, Leo Tolstoy’s granddaughter. She knew about his character but still married him. It was very similar to her own mother, who devoted her life entirely to her husband Leo Tolstoy (and we know, the guy was a bit unhinged). The marriage with Sergei was short, literally only a few months before his death. In his usual manner Sergei wrote a note: “Forgive me, I have already lived my whole life with you, I no longer love you,” and thought that was that. As history would show, he did not manage to divorce (they married in September 1925, he died in December 1925).

After this note Sergei decided he urgently needed to leave Moscow and chose to go to the Caucasus. On the train, drunk as usual, he got into an argument with a diplomatic courier and allegedly burst into the courier’s compartment trying to steal secret documents. This incident ended up in a Cheka protocol and state case. And we already remember that thirteen cases were open against him, he was under surveillance, and the Soviet press wrote unflatteringly about him, condemning his tavern lifestyle. In attempts to hide from the Cheka he was advised to check himself into a psychiatric hospital, where he wrote poems in the ward and tried to be treated for alcoholism, but everything was useless.

Anatoly Mariengof, “About Sergei Yesenin”:

In the last months of his tragic existence, Yesenin was a human being for no more than one hour a day.

After the first, morning shot of vodka, his consciousness already darkened.

And after the first, as an iron rule, came the second, third, fourth, fifth…

From time to time Yesenin was placed in a hospital, where the most famous doctors treated him with the newest methods. They helped just as little as the oldest methods, which were also tried on him.

Anatoly Mariengof, “A Novel Without Lies,” autobiography:

A very beautiful girl walked down the corridor. Blue, large eyes and unusual hair, golden like honey.

“Everyone here wants to die… that Ophelia hanged herself with her own hair.”

Then Yesenin led me into the reception hall. He showed chains and shackles in which patients had once been restrained; drawings, embroidery, and painted sculptures made of wax and bread crumb.

“Look, Vrubel’s painting… he was here too…”

Yesenin smiled:

“Just don’t think – this isn’t the madhouse… the madhouse is next door.”

He led me to the window:

“That building over there!”

Through the white, snowy foliage of the December park, the lit windows of a welcoming landowner’s house looked out cheerfully.

In December 1925 Yesenin arrived in Leningrad*. From the station he went to friends, found no one, and checked into the Angleterre Hotel. For two days acquaintances visited him, they drank and laughed. The last to see him was Wolf Ehrlich.

The next day Yesenin was found dead, hanging from a heating pipe in his room.

Being such a bright personality, his death gave rise to many rumors, and to this day people argue: suicide or murder. There is no definite answer. From my side, it was suicide. If the Cheka had wanted to kill him, they would not have staged such a farce. Many memoirs confirm the straightforwardness and absolute lack of principles and cruelty of the Chekists. They simply had no reason for such performances. But that Yesenin was in deep depression and a kind of personal crisis… this is obvious to me from his works. In any case, the fact is simple and harsh: a talented man burned out too quickly.

After her husband’s death, Sofya devoted her life to collecting and preserving Yesenin’s memory and supervised the compilation and publication of his complete works in four volumes.

*Don't be confused about location. City it was renamed several times. Saint-Petersburg (original name before revolution) -> Petrograd (first years of revolution, instead of german "burg" they needed more patriotic russian "grad", same meaning tho – city of Peter) -> Leningrad (after 1924, we all know who and why) -> Saint Petersburg (now, back to the roots)